This article originally appeared in journal Technicalities, Vol. 41 Num. 2 March / April 2021.

Yoel Kortick, Senior Librarian, Ex Libris

Over the past few decades libraries have moved from collections of books and other print media to complex collections of print and electronic resources. By looking at historical trends it is possible to conjecture what the future of these collections will look like. There are many different ways of looking at the data that reflect library collecting trends. I have looked at the way libraries spend their money. There are relatively few publications that focus on comparing expenditure trends for physical and electronic resources. However, in looking at expenditure and usage trends over a ten year period, one can posit a direct correlation between the resource type purchased and the type used.

Trends: Physical and Electronic

Historically speaking, studies that focused on library usage tended to concentrate on three general areas: reference queries, circulation of physical materials and usage of electronic materials, and gate counts (how many people enter the library and when). These metrics are useful, but lacking in precision. Patrons may use library services without ever passing through a library’s gate. Physical items may be used, but never loaned. Usage of electronic material is often measured using COUNTER reports, but many institutions only load partial COUNTER reports and only for certain vendors.¹

Another way to look at the relative usage of physical and electronic materials is by comparing library expenditures for the two. Establishing a clear correlation between changes in expenditure for a specific resource format and usage of that format is beyond the scope of this article (though it is planned for a future publication by this author).

I drew on aggregated anonymized data from ten randomly chosen academic institutions across the United States. While it is possible to look only at a subset of these institutions, for example by geographic location or discipline, my intention was to obtain as broad a picture as possible. Furthermore, by not focusing on a specific subset of the institutions, their anonymity is ensured.

The data used for the study include percentages of expenditures for physical verses electronic format from calendar year 2010 to 2019, inclusive (full years only, as of November 2020). With this data, one will be able to see not only if electronic resource usage has increased, but how much. Has it increased since 2010 in a steady, gradual manner? Did it peak and come down? Or perhaps it peaked and remained steady? Also, can one apply a forecast algorithm to predict what will happen in the coming years? Though perhaps in these unique times, created by COVID-19, a standard forecast algorithm would not be enough.

Literature Review

In his February 2011 article, “Preparing for the Long-Term Digital Future of Libraries,” Marshall Breeding considered changes that might take place in the subsequent decade. He correctly surmised, “The obvious changes to anticipate involve major shifts toward digital formats, distributed through license arrangements, rather than physical materials available for purchase.”²

As early as 2008, in a study on library use from the 1990s to 2006, Charles Martell stated, “Use of the physical collections and services of academic libraries continues to plummet, with some exceptions, while use of electronic networked resources skyrockets.”³

One study specifically mentioning expenditures for physical and electronic resources is that by Jennifer Gerke and Jack M. Maness, which was conducted at the University of Colorado at Boulder (UCB).4 While expenditures were not the main focus of the study, the following fact is noted: “The University Libraries at UCB in recent years began to spend a majority of the materials budget on electronic, as opposed to print, resources (over 56% in Fiscal Year 2007–2008). Reallocating monies in this manner appears to be in concert with patrons’ desires.”⁵

No review of the literature on library resource usage would be complete without taking the impact of COVID-19 into account. It is generally assumed, and backed up by data, that COVID-19 restrictions have contributed to an increase in the use of electronic resources. Regarding this phenomenon, Denise A. Garofalo writes in her study “Tips from the Trenches”

that all libraries, regardless of type, have found ways to highlight the digital and electronic resources available to their users as we made this rapid and unplanned switch to remote everything. As we transition back to our physical buildings, maintaining the awareness of all the e-resources of the library will no doubt be a priority.⁶ The heightened “awareness of all the e-resources of the library” will surely increase electronic resource usage going forward.

The Crossover

At the time of this research (November 2020), there were 948 institutions in the United States using Ex Libris Alma, a uniquely comprehensive cloud-based software as a service (SAAS) library services platform (LSP). Data from these institutions, for those of whom there is at least ten years of transaction data, was processed with Alma Analytics to identify expenditure trends. Alma Analytics has the capability, for example, to measure, track, and differentiate between expenditures for physical and electronic materials.

It is important to note that all the data were aggregated and completely anonymized, such that it was at no time possible for any researcher, the author of this article, or anyone else to identify the results from a specific institution. For further anonymity, percentages were used instead of actual monetary amounts; i.e., the percent of a library’s collection outlays expended on each type of resource (physical or electronic).

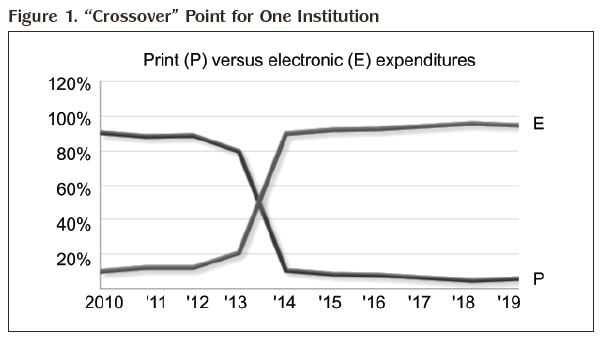

Typically, expenditures for physical format material in 2010 exceeded those for electronic format material. By 2019, however, expenditures for electronic formats were greater. The “crossover,” when expenditures on electronic resources surpassed those for physical materials, usually occurred between 2013 and 2016. Figure 1 shows the crossover point for one institution, which began spending less on print and more on electronic formats between 2013 and 2014.

History and Trends

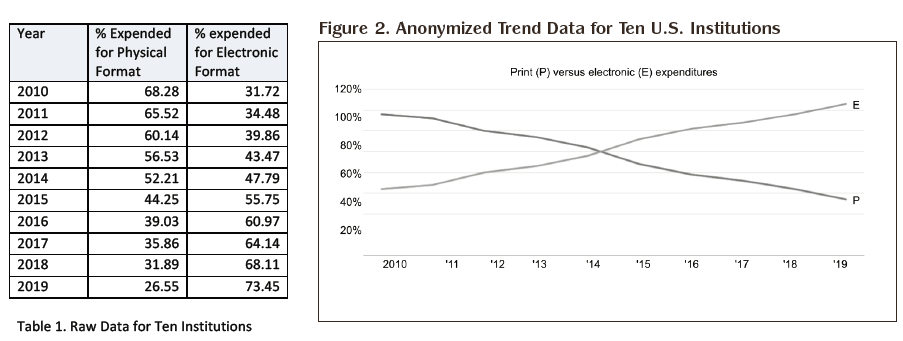

Ten institutions were randomly chosen for the study, and their combined anonymized expenditure data was aggregated by year into one table and graph. This process was carried out multiple times, with a different set of ten institutions each time, yet the resulting data was remarkably similar in each case. While the actual percentages differed slightly, the trends remained the same.

The table of anonymized, aggregated data was uploaded to Data Visualization (DV), which is part of the Oracle Analytics Server (OAS) used by Alma. The various visualizations made it easy to identify trends, while a forecast could be created using the DV’s integral features. Table 1 shows the raw, aggregated, and anonymized data for ten U.S. institutions.

The general trend is that, from 2010 to 2019, expenditures for electronic formats have increased and those for physical formats have decreased. With DV, one can see this trend represented in a line graph (Figure 2).

The data clearly support the conclusion that academic institutions in the United States have steadily decreased their expenditures for physical resources, while steadily increasing expenditures for electronic resources. By extension, one could assume patron use of resources in electronic formats also has increased relative to their use of physical materials.

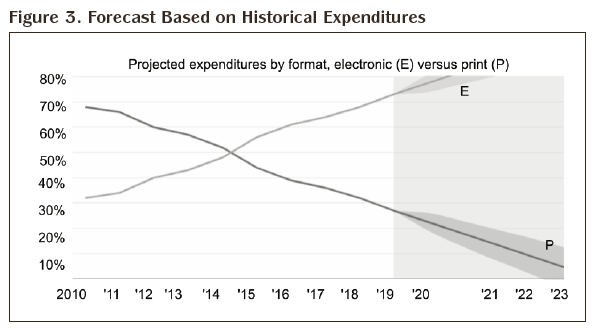

It is possible to forecast what is likely to happen with library expenditures in the coming years. The trends established by these historical data strongly suggest that expenditures for resources in a physical format will continue to decrease, while expenditures for electronic-format materials will continue to increase; see Figure 3.

Conclusion:

A Watershed Moment

Empirical evidence indicates that academic institutions in the United States have increased library expenditures for electronic resources and decreased expenditures for physical resources. According to the forecast, this trend will continue. However, a factor not taken into account by forecasting algorithms is the impact of COVID-19. As noted above, the pandemic has increased awareness of electronic resources, which can be expected to cause increased use of those resources in the coming years, especially if potential patrons remain off-campus and access to the physical library remains limited. Such a situation would prevent many people from using and borrowing physical items from the library.

I think that the current pandemic will prove to be a watershed moment in terms of expenditures for and patron usage of physical and electronic resources. Many libraries are currently discovering that their patrons’ needs can be met without ordering and processing large numbers of physical materials. Three factors will contribute to a sustained increase in the use of electronic materials even after the pandemic: processing an increasing quantity of electronic materials can be done remotely, electronic materials do not require additional space in the library or open shelves, and, most importantly, electronic materials can be accessed by patrons from anywhere.

Does this mean print collections will disappear entirely? I think not; there is still much that libraries will do, and collections that patrons will want, that remain tangible. But the data examined here suggest continued growth of electronic resources in library collections. A follow-up study looking at actual usage in the coming years would be able to examine the validity of this assessment.

References and Notes

- COUNTER provides a “Code of Practice,” a standard that enables publishers and vendors to count the use of electronic resources and ensures they can provide their library customers with consistent, credible and comparable usage data. See COUNTER, “About COUNTER,” www.projectcounter. org/about (accessed Jan. 29, 2021), https://www.projectcounter.org/.

- Marshall Breeding, “Preparing for the Long-Term Digital Future of Libraries,” Computers in Libraries 31, no. 1 (Jan./Feb. 2011): 24-26.

- Charles Martell, “The Absent User: Physical Use of Academic Library Collections and Services Continues to Decline 1995–2006,” The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34, no. 5 (Sept. 2008): 400-407.

- Jennifer Gerke and Jack M. Maness, “The Physical and the Virtual: The Relationship between Library as Place and Electronic Collections,” College & Research Libraries 71, no. 1 (Jan. 2010): 20-31.

- Ibid., 20.

- Denise A. Garofalo, “Tips from the Trenches,” Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 32, no. 3 (Sept. 2020): 218-20.